Every now and then Ron will answer your questions. Your questions can be about Ron, his life, his books, writing… Use the Contact form to submit your questions

Every now and then Ron will answer your questions. Your questions can be about Ron, his life, his books, writing… Use the Contact form to submit your questions

Q: What was the hardest chapter you’ve ever written? – Tom K.

“To survive trauma, one must be able to tell a story about it.”

Natasha Trethewey

A: For me, it was the Dolores chapter in If Pain Could Make Music, Book I, chapter 17.

When I wrote that chapter, I felt like a juggler who had a spinning plate on his head and a spinning plate in each hand while standing on a ball. The chapter was fraught with emotional confusion that I had to weave into the narrative as naturally as possible—fear, desire, pride, and sentiment. Viewed from Lemeilleur’s vantage, Dolores’s abject nakedness becomes an ambiguous stimulus that elicits unconscious emotions and internal conflicts. Lemeilleur thoughts are influenced by feelings he doesn’t understand. (He is about eleven years old, while Dolores is twelve.) He wavers when he wonders where his urge to be tender comes from. And why does pity put a bridle on his desire?

As Lemeilleur examines Dolores’s nakedness, he flashes through his reading of Lolita,

comparing Dolores’s honey-brown belly to little Lolita’s soft covering of apricot lanugo.

It’s a quirk in Lemeilleur’s personality that he has to hold Nabokov’s hand as Lemeilleur goes through the trials of his childhood. Lemeilleur derives a moral strength when he alludes to literature and art, which is a symptom of his trauma-damaged soul: You can’t believe in your own story.

Then Lemeilleur sloshes into a sentimental description of Dolores’s knees, which relaxes him for what comes next—her labial lips. Very wary of these lips, about which he has heard many stories of their destructiveness, he proceeds with his examination. To his surprise, the lips don’t look vicious, like a bear trap, as his father had told him. No, they appear docile. At which point Lemeilleur has a minor epiphany—he’s looking at the riddle of life—the conjunction of love and lust!

The solemn moment is broken when his male friends bang on the bedroom door, demanding to know if he’s doing it, which makes Dolores laugh, which makes Lemeilleur paranoid. He redoubles his efforts and moves his hand up her leg until his fingertips graze her labia. Her whole body tightens. This is the climax of this scene of two sexually disturbed children.

At heart, Lemeilleur is a good kid, but he lives in a culture that is black and blue with trauma. Still, he says to Dolores, “I’m not going to hurt you.” By now Lemeilleur wants to extricate himself from this situation without losing face.

But Dolores complicates everything when she starts to cry. So dismal is her self-respect, she is hurt by Lemeilleur’s lack of desire to use her.

Lemeilleur reels back: He sees her, a hurt girl; he feels tender. But the baboons bang on the door again. The magic moment is over. Lemeilleur asks Dolores to lie: Tell Boris I did it. To Lemeilleur’s surprise, Dolores tells him Boris asked her to do the same thing!

Now Lemeilleur regrets not having adored and kissed her.

Dolores gets dressed and tells Lemeilleur not to worry, “we’ll do it one of these days.” “How do you know?” Lemeilleur shoots back bitterly, and she says, “I like you.”

This chapter still brings a tear or two—just kids on the cusp of meaning, in spite of all else that is wrong with them.

“While trauma can be hell on earth, trauma resolved is a gift

of the gods — a heroic journey that belongs to each of us.” Peter A. Levine

What makes literature literature? – Bruce T.

Literature is the imaginative experience that, artfully and aesthetically, takes people outside their everyday reality, and moves them through artistic expressions of metaphor, symbolism and structure to explore the nature of human experience in the context of universal themes, such as love, suffering and trauma.

Significant literature remains relevant and meaningful across time and cultures, resonating with readers on emotional and intellectual levels, which encourage readers to think, feel, and imagine beyond the ordinary, making readers reflect, question, and connect with the world around them—all while they feel they are living in a dream.

Why do you write novels? – JMS

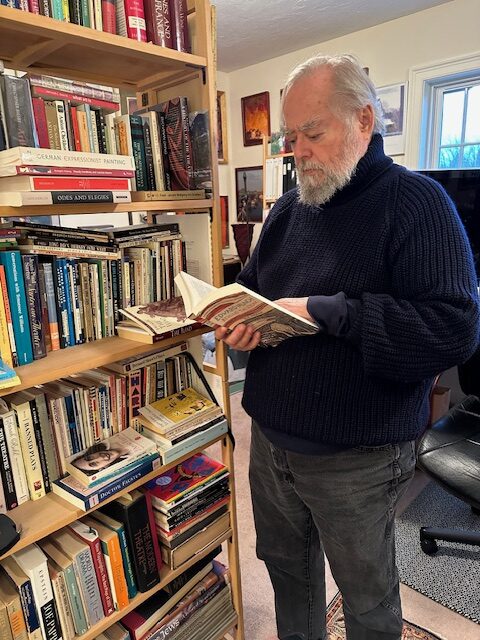

I recently ran across a few photos that, upon a couple of minutes of reflection, indicated to me significant moments in my life.

This first photo is of my exhaustion from holding on to my obsession with masculinity. Yes, that single-cylinder 441 thumper was, symbolically, my way of asserting my delusional identity.

This first photo is of my exhaustion from holding on to my obsession with masculinity. Yes, that single-cylinder 441 thumper was, symbolically, my way of asserting my delusional identity.

A few weeks after this picture, my cycle was stolen, and I was smart enough to realize that was a good thing.

I was twenty-five years old that summer and had finally graduated from college, and by November I would get my first adult job.

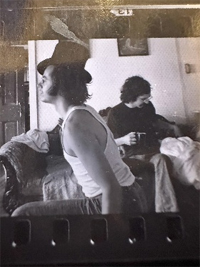

The following summer, my new spiritual mood was defined by this second picture. I had learned how to toss this top hat up into the air and catch it perfectly on my head. I was feeling much more confident now. In September I would begin my second-year teaching French in a Boston prep school.

The following summer, my new spiritual mood was defined by this second picture. I had learned how to toss this top hat up into the air and catch it perfectly on my head. I was feeling much more confident now. In September I would begin my second-year teaching French in a Boston prep school.

I am thirty years old in this next picture. I’m wearing a brown bow tie, first row, second from right. I am what Lesley College called a master teacher of mentally-challenged teenagers whose legal wrongdoings put them in special education. My classroom had a one-way mirror for graduate students to observe my teaching style and methods. The change was complete, not only am I more myself, but I’m also a model for others to look up to!

I am thirty years old in this next picture. I’m wearing a brown bow tie, first row, second from right. I am what Lesley College called a master teacher of mentally-challenged teenagers whose legal wrongdoings put them in special education. My classroom had a one-way mirror for graduate students to observe my teaching style and methods. The change was complete, not only am I more myself, but I’m also a model for others to look up to!

I believe in change. All my novels are about that belief. That’s what is behind these pictures.

What comes first, the story or the characters? – M.M.

Though characters drive the story forward, with their personalities, motivations, and conflicts, creating plot, my stories originate in a feeling—a feeling about some

circumstance that has moved me deeply and which I cannot shed unless I write about it.

It took years, many, many years, to understand my childhood, and when I did begin to get a handle on it, I had to learn how to incorporate that history into my life.

For years I pushed any realization away that this had happened to me. Eventually, I confronted myself, learned to love myself, and once I had accepted all my history

without shame, I wrote If Pain Could Make Music.

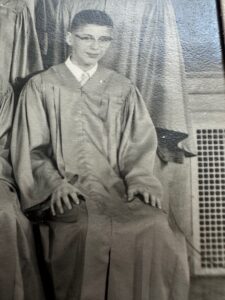

I could never look at this picture of me from 1957. It embarrassed me. A veil would drop over my eyes. The picture confused me. However, after If Pain Could Make Music, I ran across this picture and saw something different. I now remembered what I thought of myself in 1957. I thought I was a gutsy kid from the gutter, who was a self- contained person with adult-like control over my life. Now I see a vulnerable and tender child.

I could never look at this picture of me from 1957. It embarrassed me. A veil would drop over my eyes. The picture confused me. However, after If Pain Could Make Music, I ran across this picture and saw something different. I now remembered what I thought of myself in 1957. I thought I was a gutsy kid from the gutter, who was a self- contained person with adult-like control over my life. Now I see a vulnerable and tender child.

How, I asked myself, could I have been so wrong?

Today, I can cry when I look at this picture. I can live with the pain.

What follows is a letter I wish one of my parents could have written to Georges.

Madame Rimbaud to Paul Verlaine

July 1873

Monsieur,

I am writing to you with a heavy heart, as a mother who is deeply worried about her son. Arthur has returned home in a state that distresses me greatly. He is ill, both in body and spirit, and I cannot help but hold you responsible for the condition in which he finds himself. You, who are older and should have known better, have led him astray. You have taken him away from his family, from his studies, and from a life that could have been respectable. Instead, you have dragged him into a world of debauchery and instability. I cannot understand how a man of your age and experience could have so little regard for the well-being of a young man like Arthur. I beg of you, leave him alone. Do not write to him, do not try to see him. Let him recover from this madness and return to a life of peace and dignity. If you have any decency left, you will respect my wishes and cease all contact with him. I pray that you will reflect on your actions and consider the harm you have caused. Do not reply to this letter; I have nothing more to say to you.

Sincerely,

Vitalie Rimbaud